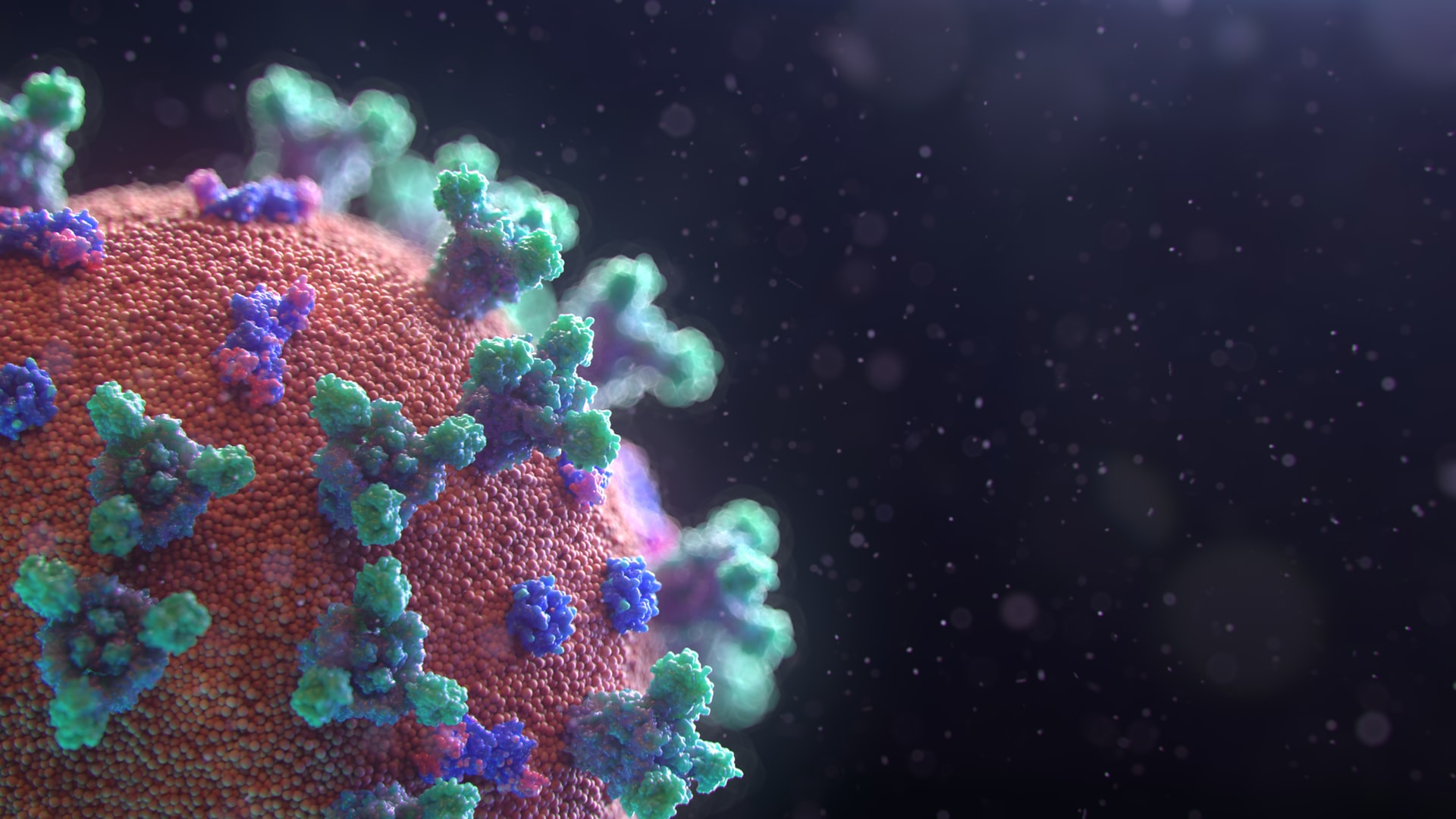

COVID-19, declared as a global pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020, has dramatically impacted the lives of every person on the planet. Not only has the virus required significant changes in the way we interact and take care of ourselves, it has also impacted the way contracts function in Canada and abroad.

While contracts are drafted to govern behaviour between two or more parties, Canadian law has long recognized that these contracts do not exist in a vacuum. There are circumstances that can occur which are beyond the control of either party which may impact a contracting party’s ability to perform their portion of a contract. These circumstances are recognized as instances of force majeure or frustration.

What is a Force Majeure Clause?

Many contracts contain provisions known as a force majeure clause. In Atlantic Paper Stock Ltd. v. St. Anne-Nackawic Pulp & Paper Co., the Supreme Court of Canada defined force majeure clauses as the following:

“An act of God clause or force majeure clause… generally operates to discharge a contracting party when a supervening, sometimes supernatural, event, beyond control of either party, makes performance impossible. The common thread is that of the unexpected, something beyond reasonable human foresight and skill…”

The devil is truly in the details when determining whether a contracting party can rely on a force majeure clause to discharge their contractual obligations. To constitute a force majeure, the language of the clause in question must explicitly capture the supervening event.

Determining the scope of the language of the clause is a fundamental starting point. In the time since the SARS outbreak in 2003, many force majeure clauses have been amended to include events such as “pandemics”, “epidemics”, and “public health emergencies”.

Courts have determined that force majeure clauses are a means of allocating the risk associated with any given contract. Absent such specific language, a reviewing Court may be reluctant to recognize the COVID-19 pandemic as a force majeure event, and instead find that such risks associated with breaching the contractual obligations were reasonably allocated by the contracting parties.

The COVID-19 pandemic must be the actual and direct reason why the relying party’s ability to perform their contractual obligation has been impaired. As such, a reviewing Court will inquire as to whether the claimed force majeure event is in fact beyond the party’s control. Force majeure clauses cannot be relied on an excuse for other reasons as to why a contracting party will be in breach of their contractual obligation.

Depending on the specific wording of the force majeure clause, the ability of the relying party to perform will be scrutinized. Indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are likely less persuasive and are unlikely to excuse a party’s contractual obligations.

A reviewing Court will also inquire into the foreseeability of the supervening event even if it is explicitly listed in a force majeure clause. While COVID-19 is likely to be found as an unforeseeable event, a contracting party that took steps in the face of reasonable evidence that the pandemic would occur, especially after March 11, 2020, may be unable to rely on the force majeure provision to relieve themselves of their performance obligations under the contract.

Finally, it must be noted that force majeure clauses can only be relied on when it becomes impossible for a contracting party to meet their contractual obligations. Contracting parties have an ongoing obligation to avoid and mitigate foreseeable impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What Constitutes Frustration of Contract?

Even if a contract does not contain a force majeure clause, parties may still have a legal defence to any breach of their contractual obligation.

In Canadian contract law, frustration takes place when an event supervenes, without the fault of either party, and for which the contract makes insufficient provision, which so significantly changes the nature of the parties’ rights or obligations from what they could reasonably have contemplated when executing the contract, that it would be unjust to hold them to its literal stipulations in the new circumstances. In such situations, both parties are discharged from further performance of their obligations under the particular contract.

Traditionally, the applicability of the frustration doctrine rested on whether the contracting parties, as reasonable parties to the contract, had contemplated the supervening event at the time of contracting, and if so, whether they would have agreed that it would put the contract to an end.

More recently, the Supreme Court of Canada has adopted a more candid approach to determining whether the frustration doctrine should apply. Specifically, in Naylor Group Inc. v Ellis-Don Construction Ltd., the Court outlined:

“The court is asked to intervene, not to enforce some fictional intention imputed to the parties, but to relieve the parties of their bargain because a supervening event… has occurred without the fault of either party… the supervening event would have had to alter the nature of the… obligation to contract… to such an extent that to compel performance despite the new and changed circumstances would be to order the appellant to do something radically different from what the parties agreed to under the tendering contract…”

While frustration has been defined as a “flexible doctrine” that is not restrictive to any formula and can be applied to all types of contracts, it remains an extraordinary remedy. Any contracting party who desires to rely on it to be excused from the performance of any contractual obligation will be subject to a very high threshold even with evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic had altered the nature of the contractual obligations.

Contract Drafting in the Future

COVID-19 will test many contracts over the coming months and years. Where contracts are unclear or silent on the attribution of responsibility during unforeseen events, there may be significant dispute or even litigation regarding these responsibilities. This can be costly and can compound the difficulties associated with navigating the rapidly changing state of the world.

When entering into a contract it is important to agree on as many of the details as possible ahead of time. This includes agreeing on items such as the inclusion of a force majeure clause, which events are to be included in the definition of force majeure, and the responsibilities of each party if such an event takes place. It is important that the contract contains clear language outlining the duties and responsibilities of each party so that there is a clear plan of action should unforeseen events like the COVID-19 pandemic arise.

At Duncan, Linton LLP, we assist clients with every stage of contractual matters, from drafting and review of commercial contracts to advising in breach of contract litigation. Our lawyers also have extensive experience in construction matters, offering insightful advice about contracts and other issues to parties at every level of the industry. Contact us online or call 519-886-3340 to make an appointment with one of our lawyers.